People’s Academy of International Law

“International Law Protects Struggles for Liberation and Emancipation”

The Right of Resistance by All Means Consistent with the Principles of the UN Charter

This draws on the work of Dr Shahd Hammouri, Kent University:

“The Palestinian People Have the Right of Resistance by All Means Consistent with the Principles of the UN Charter” (August 25, 2023). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4551668 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4551668

Status of UN General Assembly resolutions

Numerous UN General Assembly resolutions, statements by state officials as well as the First Protocol to the Geneva Conventions recognise the legitimacy of the peoples struggle by all legitimate means at their disposal including armed struggle in exercise of self- determination.

Alien domination and subjugation in all its forms including apartheid and other forms of racism impede on international peace in contravention to the UN Charter. This position was generally affirmed in the 1960 UN Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and People, as well as the 1970 Declaration on the Principles of Friendly Relations. It was further acknowledged in subsequent resolutions.

According to the ICJ in the 1975 Western Sahara advisory opinion, referred to in the 1996 Nuclear Weapons advisory opinion, UNGA resolutions can provide evidence of state practice and opinio juris, paving the way for customary international law, binding on all states. Further, given the fact that the UNGA comprises all 193 members of the UN, UNGA resolutions give a voice to states of the global south.

UNGA Resolutions since 1960

In Resolution 1654 (XVI) of 1961, “The situation with regard to the implementation of the Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples”, the UNGA declared that it was ‘convinced that further delay in the application of the declaration [on the granting of independence] is a continuing source of international conflict and disharmony, seriously impedes international co-operation, and is creating an increasingly dangerous situation in many parts of the world which may threaten peace and security.’

In Resolution 3103(XXVIII) of 1973, ‘Importance of the universal realization of the right of peoples to self- determination and of the speedy granting of independence to colonial countries and peoples for the effective guarantee and observance of human rights’, the UNGA reaffirmed ‘that the continuation of colonialism in all its forms and manifestations as noted in the General Assembly Resolution 2621 (XXV) of 12 October 1970, is a crime’.

Universal Declaration of Human Rights

The recognition of the grave illegality of alien domination and subjugation, implies that people have the right to resist it. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights stresses in its preamble that “it is essential, if man is not to be compelled to have recourse, as a last resort, to rebellion against tyranny and oppression, that human rights should be protected by the rule of law”. The wording of the preamble indicates that ‘resort to rebellion against tyranny and oppression’ is a predictable position when human rights are not protected by the rule of law.

This establishes that there can be an exception which demands a different set of rules which legitimise a recourse to force, mandated by the grave illegality.

Furthermore, underlying this position is a recognition that the denial of the people’s right of self-determination will, inevitably, generate grievance among the dominated people, eventually leading to conflict. See, for example Resolution 41/35 (1986), 10 November 1986, UN Doc. A/RES/41/35, Preamble: Policies of apartheid of the Government of South Africa, perceived acts of resistance as reactionary to the policies of the regime

In the 1960 Declaration, the UNGA noted that it is “Aware of the increasing conflicts resulting from the denial of or impediments in the way of the freedom of such peoples [peoples under foreign subjugation, domination and exploitation], which constitute a serious threat to world peace.”

For example, in the case of the South African occupation of Namibia, the Security Council Resolution 282 (1970) recognized: “the legitimacy of the struggle of the oppressed people of South Africa in pursuance of their human and political rights as set forth in the Charter of the United Nations and [in] the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. UNSC Resolution 282 (1970), 23 July 1970, UN Doc. S/RES/282 regarding an embargo on the shipment of arms to South Africa.

Likewise, in UNGA Resolution 2396 (XXIII) (1968), which was adopted unanimously but for the votes of South Africa and Portugal, the Assembly reaffirmed “its recognition of the legitimacy of the struggle of the peoples of South Africa for all human rights.”

The ICJ held in the Chagos Advisory Opinion (2019) that: “The right to self-determination under customary international law does not impose a specific mechanism for its implementation in all instances.”

Armed resistance

It has been argued that the ‘struggle’ against foreign domination in the form of resistance in pursuit of self-determination and human rights is legitimate, which leaves open the question of whether armed resistance can be considered legitimate.

In giving further content to the notion of ‘struggle’, the UNGA has repeatedly acknowledged the legitimacy of the people’s struggle ‘by all legitimate means available at their disposal’. It is arguable that the ‘means’ referenced include various expressions of self-determination including freedom of speech and political expression, and armed resistance.

UNGA Resolution 38/17 of 22 November 1983 “Importance of the universal realization of the right of peoples to self-determination and of the speedy granting of independence to colonial countries and peoples for the effective guarantee and observance of human rights” included “2. Reaffirms the legitimacy of the struggle of peoples for their independence, territorial integrity, national unity and liberation from colonial domination, apartheid and foreign occupation by all available means, including armed struggle;” 104 states voted in favour, 17 against, with 6 abstentions.

One well-known example of such armed resistance, which was perceived as a legitimate form of resistance, was the Palestinian popular uprising, ‘the intifada’, of 1988.

The recognition of the legitimacy of this uprising by the UNGA was indirectly expressed through its condemnation of retaliatory measures by Israel, and its call for solidarity with the Palestinian people. UNGA Resolution 43/21 (1988), 3 November 1988, para. 1: titled ‘The uprising (intifadah) of the Palestinian people’. See also, UNGA Resolution 44/235 (1989), 22 December 1989: regarding: “Assistance to the Palestinian People”, ‘taking into account the intifadah of the Palestinian people in the occupied Palestinian territory against the Israeli occupation, including Israeli economic and social policies and practices.”

In its 1975 Western Sahara advisory opinion, the ICJ interpreted acts of resistance by the tribes of Western Sahara as an expression of self-determination. The absence of condemnation can be taken as confirming the ICJ’s position that such armed acts of resistance against foreign domination in expression of self-determination are legitimate.

In UNGA Resolution 32/14, of 7 November 1977, with respect to Zimbabwe, Namibia, Djibouti, the Comoros and Palestine, it was stressed that self-determination is to be implemented “by all available means, including armed struggle.”

Finally, in Resolution 34/92 of 12 December 1979 on the Question of the South African occupation of Namibia, the General Assembly supported the exercise of self-determination by the Namibian people “by all means at their disposal, including armed struggle.”

The 1970 Friendly Relations Declaration stipulates that: “Every State has the duty to refrain from any forcible action which deprives peoples referred to above in the elaboration of the present principle of their right to self- determination and freedom and independence. In their actions against, and resistance to, such forcible action in pursuit of the exercise of their right to self- determination, such peoples are entitled to seek and to receive support in accordance with the purposes and principles of the Charter.”

International law of armed conflict

International Humanitarian Law (The International Law of Armed Conflict) directly acknowledges the people’s right of resistance against colonial domination and alien occupation and against racist regimes.

Article 1 of the First Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions (1977) elaborates on the Protocol’s general principles and scope of application. Its fourth paragraph stipulates:

“The situations referred to in the preceding paragraph include armed conflicts in which peoples are fighting against colonial domination and alien occupation and against racist régimes in the exercise of their right of self-determination, as enshrined in the Charter of the United Nations and the Declaration on Principles of International Law concerning Friendly Relations and Co-operation among States in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations.”

This Article, whose incorporation was hard-won by states of the global south, acknowledges the legitimacy of the people’s resistance in exercise of their right of self-determination.

The UNGA has previously ascertained the applicability of the First Additional Protocol to the occupied Palestinian territories in its request for an advisory opinion on the legal consequences arising from the construction of the wall being built by Israel. ‘Reaffirming the applicability of the Fourth Geneva Convention’ as well as Additional Protocol 1 to the Geneva Conventions to the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including East Jerusalem’ UNGA Resolution ES-10/14 (2003) 12 December 2003, preamble.

People’s Academy of International Law

Course 10: “International Law Protects Struggles for Liberation and Emancipation”

The Right of Peoples to Self-Determination

At this moment, peoples all over the world are fighting for their right to self-determination. The Palestinian and Kurdish peoples are still locked in mortal combat with their oppressors. Very close to my own home, the Irish people look forward to exercising the right to self-determination through unification, wrung from the British oppressors in the Good Friday Agreement of 1998.

Birth of the concept – as a political demand

1860s

Karl Marx (1818 – 1883)

In a letter of 20 November 1865, Marx referred to ‘[t]he need to eliminate Muscovite influence in Europe by applying the right of self-determination of nations, and the re-establishment of Poland upon a democratic and social basis’.

On 22 February 1866, the Belgian newspaper L’Echo de Verviers published a letter Marx had helped to write, containing the following language: ‘The Central Council … has founded three newspapers … one in Britain, The Workman’s Advocate, the only English newspaper which, proceeding from the right of the peoples to self-determination, recognises that the Irish have the right to throw off the English yoke.’

In a speech on Poland delivered on 22 January 1863, Marx once again referred to self-determination in strong terms:

What are the reasons for this special interest of the Working Men’s Party in the fate of Poland? First of all, of course, sympathy for a subjugated people which, by continuous heroic struggle against its oppressors, has proven its historic right to national independence and self-determination. It is by no means a contradiction that the international Working Men’s Party should strive for the restoration of the Polish nation.

1914

Vladimir Lenin – The Right of Nations to Self-Determination

“Therefore, the tendency of every national movement is towards the formation of national states, under which these requirements of modern capitalism are best satisfied. The most profound economic factors drive towards this goal, and, therefore, for the whole of Western Europe, nay, for the entire civilised world, the national state is typical and normal for the capitalist period. Consequently, if we want to grasp the meaning of self-determination of nations, not by juggling with legal definitions, or “inventing” abstract definitions, but by examining the historico-economic conditions of the national movements, we must inevitably reach the conclusion that the self-determination of nations means the political separation of these nations from alien national bodies, and the formation of an independent national state.”

1917

Vladimir Lenin – Decree of Peace – following the Bolshevik Revolution

“If any nation whatsoever is retained within the boundaries of a given state by coercion, and despite its expressed desire it is not granted the right by a free vote … with the complete withdrawal of the forces of the annexing or generally more powerful nation, to decide without the slightest coercion the question of the form of state existence of this nation, then it is an annexation…”

Woodrow Wilson – Fourteen Points –

“… peoples and provinces must not be bartered about from sovereignty to sovereignty as if they were chattels or pawns in a game”… territorial questions must be decided “in the interest of the population concerned”.

But for Wilson this only applied in Central Europe, and absolutely not to the colonial empress, including that of the USA.

UN Charter

The USSR and its allies wanted the Charter to contain a full legal “right of peoples to self-determination”, but this was successfully opposed by the colonial powers – USA, UK, France, Spain, Portugal

Article 1(2) –

“develop friendly relations among nations based on respect for the principle of equal rights and self-determination of peoples”

Article 55 –

… with a view to “… the creation of conditions of stability and well-being which are necessary for peaceful and friendly relations among nations based on respect for the principle of equal rights and self-determination of peoples.”

Self-determination as a right

1960

This UN General Assembly Resolution, one of the most important in international law, came at the peak of the anti-colonial struggles – see Gillo Pontecorvo’s classic film “The Battle of Algiers” (1965) – look at the voting, below

1960 – UNGA Resolution 1514(XV) – the Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples

1. The subjection of peoples to alien subjugation, domination and exploitation constitutes a denial of fundamental human rights, is contrary to the Charter of the United Nations and is an impediment to the promotion of world peace and cooperation.

2. All peoples have the right to self-determination; by virtue of that right they freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development.

Adopted by 89 votes to 0, with 9 abstentions (Australia, Belgium, Dominican republic, France, Portugal, Spain, Union of South Africa, UK, US)

See also Resolution 1541(XV), which sets out the options for a people exercising the right

Mainly a territorial concept of “peoples” – exceptions

- reunification of a pre-colonial entity – Morocco (French, Spanish and Tangier)

- opposition of inhabitants to maintaining colonial entity (India, Palestine, Ruanda-Urundi, British Cameroons)

- voluntary union of two separate colonies (British Togoland and Ghana, French Sudan with Senegal to form Mali – Senegal later seceded)

The right did not become a legal right until 1976 when the two International Covenants on human rights came into force. The Covenants were opened for signature on 16 December 1966.

International Covenant in Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) – now 173 states parties (the USA ratified in 1992, with many reservations), four states have signed but not ratified

International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) – now 173 states parties (the USA has not yet ratified)

The UN comprises 193 states

Common Article 1 – both the Covenants, in identical terms

1. All peoples have the right of self-determination. By virtue of that right they freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development.

2. All peoples may, for their own ends, freely dispose of their natural wealth and resources without prejudice to any obligations arising out of international economic co-operation, based upon the principle of mutual benefit, and international law. In no case may a people be deprived of its own means of subsistence.

3. The States Parties to the present Covenant, including those having responsibility for the administration of Non-Self-Governing and Trust Territories, shall promote the realization of the right of self-determination, and shall respect that right, in conformity with the provisions of the Charter of the United Nations.

Note that this right is not confined to colonial peoples – but many States insisted that there is no right to secede

See the UN Human Rights Committee’s General Comment 12 of 1984:

The right of self-determination is of particular importance because its realization is an essential condition for the effective guarantee and observance of individual human rights and for the promotion and strengthening of those rights. It is for that reason that States set forth the right of self-determination in a provision of positive law in both Covenants and placed this provision as article 1 apart from and before all of the other rights in the two Covenants.

1970

UNGA Resolution 2625(XXV) – the Declaration on Principles of International Law Concerning Friendly Relations and Co-operation among States in Accordance with the Charter of the United Nations

This Resolution was adopted without dissent on the 25th anniversary of the UN Charter – it recognises the rights of “all peoples” to SD; but – Paragraph 7 – affirms territorial integrity of

“… States conducting themselves in compliance with the principle of equal rights and self-determination of peoples … and thus possessed of a government representing the whole people belonging to the territory without distinction as to race, creed or colour..”

The International Court of Justice

The Court has decided a number of key cases on self-determination

Namibia Advisory Opinion (1971)

“…the subsequent development of international law in regard to non-self-governing territories, as enshrined in the Charter, made the principle of self-determination applicable to all of them”

Western Sahara Advisory Opinion (1975)

“… the principle of self-determination as a right of peoples, and its application for the purpose of bringing all colonial situations to a speedy end”. Judge Hardy Dillard – “It is for the people to determine the destiny of the territory, and not the territory the destiny of the people.”

The principle of uti possidetis juris – means that existing boundaries should not be disturbed – it was developed during the Latin American wars of independence against Spain and Portugal

1964 OAU Cairo Resolution – status quo to be preserved on African boundaries

Burkina Faso v Mali (1986) –

“while at first sight there is a conflict between s-d and uti possidetis, the latter does not detract from the former. Judge Abi-Saab – without the stability of frontiers, s-d is but a mirage.”

Guinea-Bissau v Senegal (1990)

East Timor Case (Portugal v Australia) (1995)

“Portugal’s assertion that the right of peoples to self-determination, as it evolved from the Charter and from United Nations practice, has an erga omnes (binding on all states) character, is irreproachable.”Also – “For the two parties, the Territory of East Timor remains a non-self-governing territory and its people has the right to self-determination.”

Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory (2004), Para 88

The Court also notes that the principle of self-determination of peoples has been enshrined in the United Nations Charter and reaffirmed by the General Assembly in resolution 2625 (XXV) cited above, pursuant to which “Every State has the duty to refrain from any forcible action which deprives peoples referred to [in that resolution] . . . of their right to self-determination.” Article 1 common to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights reaffirms the right of al1 peoples to self-determination, and lays upon the States parties the obligation to promote the realization of that right and to respect it, in conformity with the provisions of the United Nations Charter.

Para 155

The Court would observe that the obligations violated by Israel include certain obligations erga omnes… The obligations erga omnes violated by Israel are the obligation to respect the right of the Palestinian people to self-determination, and certain of its obligations under international humanitarian law.

Legal consequences of the separation of the Chagos Archipelago from Mauritius by the United Kingdom in 1965 (2019)

The ICJ re-stated that ‘since respect for the right to self-determination is an obligation erga omnes, all States have a legal interest in protecting that right’. The ICJ held that the United Kingdom violated this right when it separated the Chagos Islands from Mauritius prior to the latter’s independence in March 1968.

State of the art

1991: Aftermath of the break-up of former Yugoslavia, led by Slovenia in June 1991

On the 27 August 1991, the European Community and its Member States, at the same time as convening a peace conference on Yugoslavia, created an Arbitration Committee. The Committee was chaired by Robert Badinter, President of the French Constitutional Council, and also the Presidents of the German and Italian Constitutional Courts, the Belgian Court of Arbitration and the Spanish Constitutional Tribunal (the UK has no constitutional court)

Four opinions were delivered on 14 January 1991.

They were concerned with the question of whether the Republics of Croatia, Macedonia and Slovenia, which had formally requested recognition by the Community and its Member States, had satisfied the conditions laid down by the Council of Ministers of the European Community on the 16 December 1991: respect the UN Charter, guarantee rights for minorities, accept all existing frontiers that could only be changed by peaceful means.

The UN Charter extends the right of self-determination to all peoples. However, it neither defines what is to be understood by the word ‘peoples’, nor does it lay down rules as to how this right is to be exercised; a right which so far has been successfully invoked by colonial peoples only.

The Badinter Committee was thus correct to assert that ‘in its present state of development, international law does not make clear all the consequences which flow from this principle’. Nevertheless, through its Opinions it contributed to a more precise definition of its attributes.

The Committee, without an express statement to that effect, linked the rights of minorities to the rights of peoples. Within one State, various ethnic, religious or linguistic communities might exist. These communities would have the right to see their identity recognized and to benefit from ‘all the human rights and fundamental freedoms recognized in international law, including, where appropriate, the right to choose their national identity’.

These are ‘imperative norms’ binding all subjects of international law, and, which could one day be applied to protect, for example, the rights of Gagauz or Chechens without entailing the break-up of Moldova or Russia. One dare not even consider Corsicans or even Basques…

More importantly, the Committee noted that Article 1 of the two 1966 International Covenants on human rights establishes that ‘the principle of the right to self-determination serves to safeguard human rights’. This signifies that ‘by virtue of this right, each human entity might indicate his or her belonging to the community (…) of his or her choice*.

1998: the “state of the art”

20 August 1998 Canadian Supreme Court Reference re Secession of Quebec

http://www.lexum.umontreal.ca/csc-scc/en/pub/1998/vol2/html/1998scr2_0217.html

The court ruled that a simple vote in Quebec is not enough to allow the French-speaking province to legally separate from the rest of Canada. However, the unanimous opinion by nine justices did not go so far as to declare Canada indivisible. If a clear majority of the people in Quebec want to secede, the justices said, the rest of Canada would be obliged to negotiate the terms of secession as though it were an amendment to the constitution.

The Supreme Court also found that there is no right to unilateral secession in international law except for colonies and oppressed people, which it said does not apply to Quebec. If the province tried to secede outside Canada’s constitutional framework, the court warned, the international community would be likely to reject the action as illegitimate.

Bill Bowring, Birkbeck College

The Migration Conference 2025, University of Greenwich. London

Distinguished Keynote – Plenary Discussion Session

1. I’m a human rights lawyer. My primary interest since starting in academe has been collective rights, the rights of people, the right of peoples to self-determination. But I don’t believe that law is or can be emancipatory. Let me explain.

2. Self-determination for me is not the argument, made, for example, by Miller and Walzer, that communities have the exclusionary right to self-determine their identities and membership. The right of peoples to self-determination began in the 19th century with anti-colonial and anti-imperial struggles, Ireland, Poland, India, Algeria…

3. Over the years I have represented at the European Court of Human Rights at Strasbourg many Kurds against Turkey, and many Chechens against Russia

4. The ECHR was the brain-child of Winston Churchill, as the ideological counterpart of NATO in the Cold War, and to prevent any return of socialism in Britain. But there it is, there are useful things a lawyer can do. The result of hundreds of victories against Turkey and Russia is not that Kurds are free, or that Chechens do not suffer under a Putin-financed dictator. But the applicants wanted the undeniable truth of what had befallen them.

5. And borders are very much in issue. Migration across borders.

6. So as a matter of curiosity I was drawn to the burgeoning literature on Open Borders – John Reece’s collection in 2019 and John Washington’s manifesto in 2023; and No Borders – especially Bridget Anderson and her colleagues “Why No Borders” in Refuge in 2009.

7. The geographer Harald Bauder published in 2015 a useful survey.

8. Open Borders – citing Joseph Carens in 2000, the open borders argument is not really intended as a concrete policy recommendation. “It has rather a heuristic function revealing to us something about the specific character of the moral flaws of the world.”

9. No Borders – altogether different kind of politics

a. not a utopian image of the future without borders

b. rather a focus on current policies and everyday practices – as in the special edition of Refuge

10. Time for a reality check! Starting with border walls.

11. John Washington focuses in particular on the border walls. Writing in 2023 there were 63 border walls, with 2,250 immigration detention centres, and a displaced population of 110 million people.

12. However, he adds

a. In the first century of the USA there were no federal migration laws

b. No fences or walls along the US-Mexico border until the late 1990s

c. In 1990 there were only 15 international border walls, now in their 80s. Washington fully expects that this number will fall to 15 again and probably zero

13. But what about the history of borders? In the scholarly literature they are often treated as fixed, even sacrosanct.

14. However:

a. The current international borders of Africa are the legacy of colonialism and the Congress of Berlin, in the words of the late Basil Davidson, “the black man’s burden: the curse of the nation state”.

b. Borders in the Americas reflect European colonialism, and Donald Trump would like to eliminate the border between USA and Canada. In the Mexican-American War (1846-1848) the US acquired vast territories, including present-day California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, and parts of Colorado and Wyoming. Trump’s wall is irrelevant `- in the southern states, the cities of Albuquerque and Phoenix (both nearly 50%), a growing Hispanic/Latino population. Mexico has already reconquered much of the territory lost in the 19th century.

c. The British Empire carried out Partition in Ireland, India and Palestine, with lasting bloody consequences. The border between the Republic and the Occupied Six Counties will disappear in my lifetime

d. The Far East suffers the effects of British, French, Dutch, and US colonialism, with continuing instability and blood shed

e. Poland was partitioned three times in the 19th century, was partitioned then occupied by the USSR in the 20th, and at the end of WWII shunted several hundred kilometres to the west. Lvov became Lviv, Breslau became Wroclaw

f. During my lifetime the former Yugoslavia, the former Czechoslovakia, the former DDR, and the former USSR, have all vanished. The former UK or FUK, will follow.

15. Now there are two raging conflicts. Russia believes there is no border with Ukraine; Israel asserts that Palestine, despite partition, does not exist. There are insect-like Arabs to be eliminated form territory extending to Damascus, according the the Messianic Kehanists now in power.

16. Last but far from least I mention climate change, especially that Donald Trump is hell bent on destroying all attempts at stopping or slowing catastrophic change. In her 2022 book “Nomad Century: How to Survive the Climate Upheaval”, Gaia Vince concludes that “people will move in their millions”. To say the least. I believe that human beings if forced to be on the move, cannot be stopped.

26 March 2025

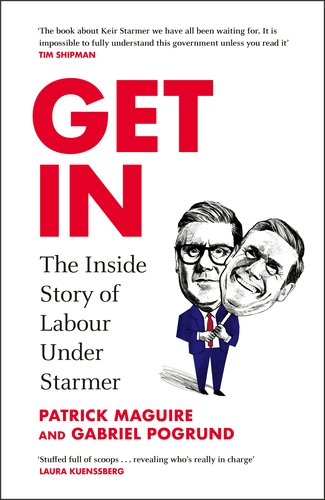

Bill Bowring reviews Get In: The Inside Story of Labour under Starmer by Patrick Maguire and Gabriel Pogrund, published by The Bodley Head.

In her front cover endorsement Laura Kuenssberg says “Stuffed full of scoops…revealing who’s really in charge.” And that is not Sir Keir Starmer KC, former Director of Public Prosecutions, 2008 to 2013, the job, as Chief Prosecutor, in which he was evidently most at home. The authors, a political columnist for The Times, and Whitehall Editor at the Sunday Times respectively, conclude that: “Their political project was predicated on this unpolitical leader doing as he was told.”

Who were “they”?

There is no question that the hero of this book is Morgan McSweeney, Downing Street Chief of Staff since October 2024, and Labour Party campaign manager from November 2022. McSweeney has no fewer than 59 entries in the Index, and appearances on almost every page. Right at the start, McSweeney is introduced, at a meeting with Jeremy Corbyn, no less, at a meeting in April 2019, as “the man from West Cork… the mastermind of a deception without precedent in British politics.”

But even earlier in the book an inanimate hero appears, “a south London dinner table”. This object makes many appearances in the book, and is of particular interest to me.

In 1978, I was elected to Lambeth Council as Councillor for Herne Hill, which included Railton Road, the centre of the first Brixton riots in April 1981. I was encouraged to stand for election by colleagues at the Brixton Advice Centre in Railton Road, where as a recently qualified barrister I volunteered as a housing adviser, and went on to represent squatters in court. This brought me into sharp conflict with the Labour leader Ted Knight, a true Municipal Socialist, although we went on to become comrades and friends. I was elected for a second four-year term in 1982, for Angell Ward, and in 1986 was, with Ted and my other Labour comrades, surcharged £106,000 and banned from holding office for five years, for “wilful misconduct”, resisting Thatcher’s devastating attack on local government. The Greater London Council was abolished by her in the same year.

Why the dinner table?

All is revealed in Chapter 4. “Labour’s strategy was really written by the kitchen cabinet which met in secret on Sunday evenings at the Kennington home of Roger Liddle, a Labour peer and old friend of Peter Mandelson’s from their days as councillors under Ted Knight.” Another key conspirator was Wes Streeting, “the smooth talker all present hoped would one day lead the party.”

Liddle and Mandelson were elected to Lambeth Council with me in 1978, and were close cronies, united in their hatred and contempt for the left in the Lambeth Constituency Labour Parties. Indeed, in 1981, Liddle was a founder member of the Social Democratic Party (SDP) and left Labour until the SDP was dissolved in 1988. He re-emerged as a Special Adviser to Tony Blair in 1997, and on 19th June 2010 became a Labour Peer as Baron Liddle of Carlisle. He was introduced in the House of Lords by… Lord Mandelson and Lord Rodgers, another founder of the SDP and later Lib Dem peer.

Mandelson did not stand in 1982, did not join Liddle in the SDP, rose in the Labour Party, was close to Blair, and was famously obliged to resign government positions in 2000 (because of a loan which enabled him to buy a house in Notting Hill) and in 2001 (a passport application scandal). He went on to become EU Trade Commissioner, and in 2008 was also created a Baron. Now, as a Starmer crony, he has a really dreadful job, UK Ambassador to Washington.

The next sighting of the dinner table is virtual, an online meeting of Liddle’s supper club on 4th May 2020, in lockdown. Some months later, “over dinner at Roger Liddle’s on 8th March”, McSweeney described the tuition fees pledge as a “bribe”. McSweeney believed that identity politics was an electoral dead end. “Over dinner at Roger Liddle’s his circle had bemoaned the supposed co-option of racial politics by the Corbynite left.”

At the same meeting, McSweeney told “his audience at Roger Liddle’s supper club” that the EHRC inquiry, engineered with help of his work with the Jewish Labour Movement, would be Starmer’s Clause IV moment, “the definitive, irreversible break from the past.”

In October, “over dinner at Roger Liddle’s, [McSweeney] apprised his friends of the political strategy that could – would? – make Starmer prime minister within 5 years.” And in “early December he returned to Roger Liddle’s dining table. He spoke with a new optimism. Corbyn had been humiliated.” Later, in early December 2020, McSweeney again enlightened his friends at Roger Liddle’s.

Fast forward to May 2021, and “As well as predicting a defeat in Hartlepool, McSweeney had told his friends at Roger Liddle’s dining table that the May elections would ‘test all our systems as if running a general election campaign’.” In the aftermath of Hartlepool, “news of [Angela Rayner’s] supposed ambitions had even reached Roger Liddle’s dining table…” When there was the possibility of Starmer resigning, “Neither Rayner nor Mahmood knew of the Lambeth dinners hosted by Roger Liddle at which Streeting was ever-present.”

Recounting the events of 2024, the authors reveal McSweeney’s hatchet man, “the impish Matthew Faulding, a friend and protégé of McSweeney, and regular attendee of Roger Liddle’s supper clubs.”

The two authors of this gossip-stuffed volume must have a hot line to this table, which acquires a totemic significance for them as the location of the successful plot – which never included Starmer. Or perhaps their source is the ex-SDP Baron himself.

One wonders if one should feel sorry for the pawn, Starmer himself?

Bill Bowring was a Lambeth Labour Councillor from 1978 to 1986.

Published in SCRSS Digest, Issue SD-33, Spring 2025 (journal of the Society for Co-operation in Russian & Soviet Studies)

Book Reviews

Feliks Volkhovskii: A Revolutionary Life

By Michael Hughes (Open Book Publishers, 2024, 336pp; ISBN: 978-1-80511-194-8, Pbk, £22.95; ISBN: 978-1-80511-196-2, pdf free to download at https://www.openbookpublishers.com/books/10.11647/obp.0385)

This new book is the result of the interest in Feliks Volkhovskii pursued for many years by Professor Michael Hughes of Lancaster University, searching many archives around the world (in his own words). It is extraordinarily rich in detail and digression, supported by a forest of footnotes, which at times make the text rather indigestible.

The reader will gain insights into the nature of revolutionary activity in Russia and in late nineteenth-century London, where so many Russian revolutionaries found sanctuary in exile. The most famous are Alexander Herzen (1812–1870), who lived in London from 1852 to 1865 where he published The Bell, and Vladimir Ulyanov (Lenin, 1870–1924), who, as I outline below, travelled to London on five occasions from 1902 to 1911.

Hughes, an Anglican lay reader, has written on Anglo-Russian relations, especially those between Anglicanism and Orthodoxy. His previous monograph was a biography of Randall Davidson, Archbishop of Canterbury from 1903 to 1928 (Routledge, 2017).

In his preface, Hughes writes: “I am perhaps an unlikely biographer of a revolutionary like Volkhovskii. Much of my work over the past few decades has focused on individuals who were firmly ensconced in the social and political establishment of their assorted homelands. I have also spent a good deal of time exploring the lives of conservative-minded figures who sought refuge from the chaos of modernity in an imagined world of social harmony and order.”

Volkhovskii was a lesser-known Russian revolutionary, who was born in July 1846 in Poltava in central Ukraine and died in August 1914, at the age of 68, in London. His family had a mixed heritage of Polish-speaking Catholics and Russian Orthodox. Through his close relations with household serfs, he became fluent in Ukrainian, and this helped to fuel his hatred of the Russian autocracy.

He was first arrested aged 21 in 1868, though soon released, as his activity was judged not to be revolutionary. In 1871–72 he was accused of fomenting student unrest and spent two years in prison awaiting trial, but was acquitted and moved to Odessa. He was arrested again in 1874 and taken to Moscow, and was in prison in Moscow and then St Petersburg. In 1877 he was a defendant in the ‘Trial of the 193’, was sentenced to exile in Siberia, where he spent two years, before settling in Tomsk in 1881. In 1889 he escaped first to Toronto, then in 1890 to London, where he spent the rest of his life. He initiated the Society of Friends of Russian Freedom, and its newspaper Free Russia, which attracted the support of the liberal elite.

In 1901–2 Volkhovskii became active in the Socialist Revolutionary Party (the SRs), but was already too ill to play any part in the 1905 Revolution in Russia. He was a prolific writer for newspapers and journals, especially on literature, but “seldom touched on questions of ideology or revolutionary tactics narrowly understood”.

In 1902–3 Lenin lived in London, and edited the revolutionary newspaper Iskra in the building which is now the Marx Memorial Library in Clerkenwell, where his office has been preserved. He took part in the fateful 1903 second Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP), where it split into Bolsheviks and Mensheviks. Lenin returned to London in April–May 1905 for the third Congress of the RSDLP, and in May–June 1907 for its fifth Congress, at which there were 366 delegates. His fifth and final visit was in November 1911.

In 1908, working in the British Museum Library on his Materialism and Empirio-Criticism, Lenin lived on the first floor of what is now 36 Tavistock Place, WC1 (formerly numbered 21), where – with the Mayor of Camden – I unveiled a blue plaque in 2012. The plaque, the initiative of the Marchmont Association, reads: “Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, 1870–1924, founder of the USSR, lived here in 1908.”

Volkhovskii never met Lenin, and they would have had little in common.

Bill Bowring

The International Day of the Endangered Lawyer is the day on which we highlight the plight of the lawyers all over the world who are being harassed, silenced, pressured, threatened, persecuted, tortured. Even murders and disappearances have been perpetrated. The only reason for these outrages is the fact that these lawyers are doing their job, and their professional obligations, when needed the most.

The 24th of January was chosen to be the annual International Day of the Endangered Lawyer because on 24 January 1977 three extreme-right terrorists stormed into the offices of labour lawyers working for the trade union Comisiones Obreras (CCOO) in the Calle Atocha in Madrid. They opened fire murdering three of the lawyers, Enrique Valdelvira Ibáñez, Luis Javier Benavides Orgaz and Francisco Javier Sauquillo. They also killed a law student and an administrator. The Atocha Massacre was a turning-point in Spain’s transition to democracy.

In 2010, the very first Day of the Endangered Lawyer (DotEL) was organized by the Foundation “The Day of the Endangered Lawyer”, founded by the Dutch lawyers Symone Gaasbeek-Wielinga and Hans Gaasbeek following their visit to The Philippines in 1990.

It is now organised by the Coalition for the International Day of the Endangered Lawyer. 35 lawyers organisation from around the world are members of the Coalition, including the Law Society of England and Wales, Council of Bars and Law Societies of Europe (CCBE), Institut des Droits de l’Homme des Avocats Européens (IDHAE), International Bar Association’s Human Rights Institute (IBAHRI), Federation of European Bars, Institute for the Rule of Law of the International Association of Lawyers (UIA-IROL), and the European Association of Lawyers for Democracy and World Human Rights (ELDH), of which BHRC Executive Committee member Bill Bowring is Honorary President.

The DotEL aims on the one hand, to create awareness that the practice of the legal profession in many countries involves significant risks, including that of being murdered, but it aims as well at denouncing the situation in a particular country where lawyers are victims of serious violations of their fundamental rights because of the exercise of their profession.

Every year on 24 January lawyers’ organisations dedicate this day to the endangered lawyers in a particular country: 2010 Iran, 2012 Turkey, 2013 Basque Country/Spain, 2014 Colombia, 2015 Philippines, 2016 Honduras, 2017 China, 2018 Egypt, 2019 Turkey, 2020 Pakistan, 2021 Azerbaijan, 2022 Colombia, 2023 Afghanistan, 2024 Iran, 2025 Belarus.

In 2025, the International Day of the Endangered Lawyer spotlights the persecution of lawyers in Belarus. They face pervasive systematic harassment and interference with their professional activities. Following the Presidential election and mass protests in 2020, a crackdown by the government has resulted in the targeting of lawyers, human rights defenders, journalists, and dissidents. There is a persistent and disturbing trend in Belarus where legal practitioners face escalating criminal sanctions, arbitrary detention, and systemic interference in their professional duties.

Bill Bowring, 22 January 2025

My two pennies worth: I was in Damascus twice, before the Civil War, for the second time for IADL with Palestinian lawyers for the Arab Lawyers Union Congress in 2004. I was sitting just in front of Assad (who became President in 2000), an extremely unimpressive speaker. He was a pale shadow of his father, who had had some of the remaining lustre of the Baathist anticolonial movement for Arab unity, led by Nasser, supported by the USSR. Even then it was clear that Assad Jnr’s days were numbered.

When the Civil War broke out in 2015, Assad was saved by Russian intervention on a grand scale, and Russia got the warm water naval base at Tartus and the air base at Latakia. Russia has now suffered a real blow and the loss of its massive investment in Syria. In early January 2017, the Russian Chief of General Staff, Gerasimov, said that the Russian Air Force had carried out 19,160 combat missions and delivered 71,000 strikes on “the infrastructure of terrorists”.

All four powers concerned, Turkey, Russia, Israel, and the USA, were taken completely by surprise by the HTS move out of Idlib, and the collapse of the Syrian army. Turkey is said to have given the green light to HTS, which is an enemy of the Kurds, but did not expect this result, the law of unintended consequences. What has happened is quite different from the direct Western interventions for regime change which led to the murders of Gadaffi and Saddam Hussein. What happens next is completely unpredictable.

In Socialist Lawyer, No.94, 2024-1, pp. 24-27

The Israel-Palestine conflict is deeply rooted in historical, political, and social tragedy . From the emergence of Zionism to contentious declarations and wars, and to the recent landmark International Court of Justice (ICJ) ruling, each phase of this conflict has been soaked in blood. . This article looks briefly at the history of the Israel-Palestine conflict, examines the critical aspects of the ICJ’s ruling, and explores the potential aftermath.

In 1893 Nathan Birnbaum coined the term ‘Zionism’ . Theodor Herzl’s “Der Judenstaat” (1896) catalyzed a Zionist movement, culminating in the First Zionist Congress in 1897, which explicitly aimed to establish a Jewish territory in Palestine secured by law.

The collapse of the Ottoman Empire after World War I led to the Sykes-Picot Agreement, which divided the Middle East between Britain and France but made no mention of a Jewish homeland. However, the 1917 Balfour Declaration set out British support for the establishment of a “national home for the Jewish people” in Palestine, albeit with a caveat to not prejudice the rights of non-Jewish communities. Under the League of Nations, established in 1920, Britain became the “Mandatory Power” in Palestine, as well as present-day Jordan and Iraq.

Significant Jewish immigration led to escalating tensions with the native Arab population. The uprising by Palestinian Arabs in Mandatory Palestine against British rule lasted from 1936 until 1939, demanding Arab independence and the end of the policy of open-ended Jewish immigration and land purchases, which had the stated Zionist goal of establishing a “Jewish National Home”. The Jewish population grew under British auspices from 57,000 to 320,000 in 1935. The uprising caused the British Mandate to give crucial support to pre-state Zionist terrorist militias like the Haganah,

In 1935, the Irgun, a Zionist underground military organization, split off from the Haganah. The Peel Commission’s partition recommendation in 1937 and the British White Paper of 1939, attempted to limit Jewish immigration and foresaw an independent Palestine within ten years.

After World War II, between 1945 and the 29 November 1947 UN Partition vote, British soldiers and policemen were targeted by Zionist terrorists, especially Irgun. Haganah at first collaborated with the British against them, before actively joining them in the Jewish Resistance Movement.

The Haganah carried out violent attacks in Palestine, such as the liberation of interned immigrants from the Atlit detainee camp, the bombing of the railroad network, sabotage raids on radar installations and bases of the British Palestine police. It continued to organise illegal immigration throughout WW II.

On 22 July 1946 the British Mandate HQ in the King David Hotel in Jerusalem, was bombed in a terrorist attack by Irgun. 91 people of various nationalities were killed, including British officers, Arabs, and Jews, and 46 were injured. In February 1947, Britain announced that it would end the mandate, and withdraw from Palestine and asked for the arbitration of the United Nations.

The UN’s partition plan in 1947, proposed separate Jewish and Arab states. This plan was accepted by the Jewish community but rejected by the Arab states and Palestinian Arabs, leading to the declaration of the State of Israel in 1948 and a subsequent war involving neighbouring Arab countries. During this war the new state of Israel carried out the violent displacement and dispossession of Palestinians, known as the Nakba, the Catastrophe. There were dozens of massacres of Arabs, and about 400 Arab-majority towns and villages were depopulated, with many of these being either completely destroyed or repopulated by Jewish residents and given new Hebrew names. Approximately 750,000 Palestinian Arabs (about half of Palestine’s Arab population) fled from their homes or were expelled by Zionist militias and later the Israeli army, in what is now Israel proper, which covers 78% of the total land area of the former Mandatory Palestine.

The displaced Arabs are now to be found in the many refugee camps in Lebanon, Jordan, the West Bank and especially in Gaza, where two thirds of the population are already refugees. The war resulted the annexation of East Jerusalem and the West Bank by Jordan, and the Gaza Strip by Egypt.

The United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNWRA) was established in 1949 by the UN General Assembly (UNGA) to provide relief to all refugees resulting from the 1948 conflict. More than 5.6 million Palestinians are registered with UNRWA as refugees.

After the 1967 Six-Day War Israel occupied Gaza, the West Bank, the Sinai Peninsula, and the Golan Heights. The unanimous (including the USA) UN Security Council Resolution 242 of 22 November 1967 , called for the withdrawal of Israeli troops from the occupied territories, and acknowledged the claim of sovereignty, territorial integrity and political independence of every state in the region.

The 1973 Arab–Israeli War (the Yom Kippur War) was fought from 6 to 25 October 1973, between Israel and a coalition of Arab states led by Egypt and Syria. The 1979 Egypt-Israel Peace Treaty resulted in Israel’s withdrawal from Sinai, but enabled Israel to remain in military occupation of the West Bank and Gaza, the OPTs.

Palestinian civilians are protected by the Fourth Geneva Convention of 1949, for Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War, which Israel ratified. But it has committed numerous violations, grave breaches amounting to war crimes. Even the USA acknowledged that Israel’s annexation of East Jerusalem in 1980 was illegal. The more than 300 Jewish settlements in the West Bank, and the settler-only roads which connect them, are not only illegal, and amount to apartheid, but make a two state solution impossible.

The right wing members of Netanyahu’s coalition, especially Ben Gvir, Minister for Settlements, himself a settler, and Smotrich, advocate a Greater Israel, from the River to the Sea, according to God’s covenant to Abraham for Judea and Samaria (the West Bank), and completion of the Nakba. Netanyahu has always been totally opposed to anything resembling Palestinian statehood.

The Oslo Accords of 1993 are regarded by Palestinians as another disaster, greatly increasing the number and size of illegal settlements, and creating a Palestinian Authority which is subject to military occupation and which collaborates with Israel.

This led on the Israel side to the assassination of Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin in 1995 and the Second Intifada 2000 to 2005. Israel, withdrew Israeli settlements from Gaza, and began construction of the “Separation Barrier” a more than 700 km concrete wall through the West Bank, condemned by the ICJ in 2004 as violating the right of the Palestinian people to self-determination., Hamas, encouraged by Israel’s desire to split Fatah, won the legislative election in Gaza in 2006. Instead of attempting to negotiate, Israel imposed a blockade on Gaza

There was armed conflict between Hamas and Israel, with many deaths, in 2008, 2012, 2014, 2018, 2021, 2022 and early 2023. Israeli complacency and intelligence failure enabled

Hamas lead a terrorist attack into Israel on 7 October 2023. Israel declared war on Gaza, and the horror of its invasion continues to the present day.

In January 2024 South Africa in a bold and unexpected initiative, filed a claim against Israel under the 1948 Genocide Convention at the UN’s International Court of Justice seeking interim measures (an injuction). Israel, which has ignored the International Criminal Court, was obliged to respond, as a UN member and signatory to the Convention.

After two days of public hearings on 11 and 12 January 2024, on 26 January 2024 the ICJ held that South Africa had presented a “plausible” case that Israel was violating the Genocide Convention ruling and that “the catastrophic humanitarian situation” in Gaza “is at serious risk of deteriorating further before the Court renders its final judgment.”

The ICJ ordered six provisional measures aimed at safeguarding the rights and lives of Palestinians:

- Israel shall take all measures within its power to prevent the commission of all genocidal acts, particularly (a) killing members of the group; (b) causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group; (c) deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part; and (d) imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group.

- Israel shall ensure with immediate effect that its military does not commit any acts described in point 1 above.

- Israel shall take all measures within its power to prevent and punish the direct and public incitement to commit genocide.

- Israel shall take immediate and effective measures to enable the provision of urgently needed basic services and humanitarian assistance to address the adverse conditions of life faced by Palestinians in Gaza.

- Israel shall take effective measures to prevent the destruction and ensure the preservation of evidence.

- Israel shall submit a report to the Court on all measures taken to give effect to this Order within one month from the date of this Order.

The orders stopped short of requiring Israel to “immediately suspend its military operations” in Gaza, as requested by South Africa. However, the provisional measures arguably effectively require a ceasefire in all but name, since complying with the orders that forbid the genocidal killing of Palestinians and require Israel to allow humanitarian aid into Gaza will be unworkable in the absence of one.

South Africa’s powerful submissions on 11 January were ignored in the UK mainstream media, but have been watched on Al Jazeera, the UK’s Islam Channel, and by millions all over the world, doing immense damage to Israel’s standing and credibility. Also on 26 January, following unsubstantiated allegations by Israel, the USA, UK Germany and other states which are now complicit in Israel’s crimes suspended funding to UNWRA. This was a classic “dead cat” move to distract attention from the ICJ’s powerful ruling and decision, and also further condemns the millions now crammed into southern Gaza to misery and starvation. The Haldane Society and its European Colleagues in EDH condemn the suspension, and salute the state such as Belgium, Ireland and Spain which have refused to comply.

At the time of writing, Israel must submit its report. It has already condemned the ICJ, and the UN, as antisemitic, and has rejected the decision. Netanyahu threatens continuation of the war on Gaza until 2025. Members of the Israeli government openly call for the completion of the Nakba. The horror continues.

The first words of Haldane member Blinne Ní Ghrálaigh KC’’s closing submissions to the ICj on 11 January 2024.

“In a powerful sermon delivered from a church in Bethlehem on Christmas Day (the same day Israel had killed 250 Palestinians, including at least 86 people many from the same family, massacred in a single strike on Magazi refugee camp) Palestinian Pastor Munther Isaak, addressed his congregation and the world. He said, and I quote, “Gaza as we know it no longer exists. This is an annihilation. This is a genocide. We will rise. We will stand up again from the midst of destruction as we have always done as Palestinians, though this is by far maybe the biggest blow we have received. But no apologies will be accepted after the genocide. What has been done has been done. I want you to look in the mirror and ask “where was I when Gaza was going through a genocide””. South Africa is here before this court, in the Peace Palace, it has done what it could, it is doing what it can by initiating these proceedings by seeking interim measures against itself as well as against Israel. South Africa now respectfully and humbly calls on this honourable Court to do what is in its power to do to indicate the provisional measures that are so urgently required to prevent further irreparable harm to the Palestinian people in Gaza, whose hopes including for their very survival, are now vested in this court.”

30 Years of the Russian Constitution

This article is a contribution to the Verfassungsblog debate » The Legal Tools of Authoritarianism: The Russian Constitution at 30

The question should perhaps be “what went right?”. I argue that for more than 30 years, as a result of a key provision in the Constitution, and the work of the Constitutional Court of the Russian Federation (CCRF) there were many positive changes to Russian law and practice. In 2018, I published specifically on this topic.

These advances were only possible as a result of Russia’s membership of the Council of Europe (CoE, accession on 28 February 1996, following application to join on 7 May 1992 and Parliamentary Assembly recommendation on 25 January 1996, despite the First Chechen War) and ratification on 5 May 1998, of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR).

The 1993 Constitution was adopted in inauspicious circumstances, after President Yeltsin tore up the existing constitution and stormed the White House, where the Supreme Soviet was in session. I return to this below.

Of course, on 16 March 2022, Russia was excluded from the CoE, following its all-out invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022, and ceased to be bound by the ECHR. On 23 March 2022, the Committee of Ministers (CoM) and the Plenary of the Strasbourg Court decided, separately but almost simultaneously, that Russia would cease to be a Contracting Party to the ECHR on 16 September 2022.

I have argued over the years, and most recently in a chapter in 2018, that Russian ratification of the ECHR was in no sense a “legal transplant”, but was correctly understood in Russia as a restoration of the Great Legal Reforms of Tsar Alexander II of 1864, including jury trial, an independent Bar, a reduced role for Prosecutors, and procedural rights, following Russian defeat in the Crimean War (1854-1856), and his abolition of serfdom in 1861, several years before the USA abolished slavery.

The Constitutional Court and the new Constitution

The Law on the Constitutional Court of the RSFSR (within the USSR) was signed by President Yeltsin, who had been elected President of the RSFSR, on 12 June 1991. The USSR collapsed in December 1991.

The Court started work in January 1992, almost immediately after the collapse of the USSR. From 6 July 1992 to 30 November 1992 the Court was occupied by the Case of the Communist Party, which did not produce the hoped-for (by the applicants) definitive condemnation of the Communist Party, a Russian Nuremberg, but instead in a compromise decision ruled that President Yeltsin rightly dissolved the highest bodies of the Party, but also ruled that the Party could continue to exist at the local level. There was no “drawing of a line” under Russia’s Soviet past.

The CCRF sat all night following Mr Yeltsin’s decree of 21 September 1993 declaring the Congress of People’s Deputies and the Supreme Soviet dissolved and held that his actions violated the Constitution. The Court was suspended by Yeltsin on 7 October 1993, after he tore up the 1978 Constitution, disbanded parliament, and finally shelled the White House, the seat of the parliament. As Alexei Trochev put it in Judging Russia The Role of the Constitutional Court in Russian Politics 1990–2006, “[i]n response to the Court’s finding that Yeltsin had violated the constitution, Yeltsin shelled the parliament’s building and suspended the [CCRF] by Decree 1612 of 7 October 1993.”

The new Constitution was adopted by a referendum of 12 December 1993. The official result of the referendum was that 54.8% of the electorate had voted, and of those, 58.4% had approved the new Constitution, which came into force on 24 December 1993. Not a resounding success.

In July 1994 a new Law on the Constitutional Court was adopted. However, the new Constitutional Court started working only in February 1995.

The status of international law including the ECHR

The provision of Article 15(4) turned out to be of special importance:

4. Universally recognized principles and norms of international law as well as international agreements of the Russian Federation should be an integral part of its legal system. If an international agreement of the Russian Federation establishes rules, which differ from those stipulated by law, then the rules of the international agreement shall be applied.

The whole case law of the ECtHR became, in 1998, part of Russian law (Russia being a “monist” state), and was frequently cited in the CCRF.

The apotheosis of this new relationship seemed to have truly arrived with the Resolution of the Plenum of the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation of 10 October 2003, binding on all lower courts. The Resolution was entitled ‘On application by courts of general jurisdiction of the commonly recognized principles and norms of the international law and the international treaties of the Russian Federation’.

This Resolution was followed ten years later on 27 June 2013 by the Resolution ‘On Application of the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms of 4 November 1950 and Protocols thereto by Courts of General Jurisdiction’. Paragraph 2 of the Resolution stated:

2. As follows from Article 46 of the [ECHR], Article 1 of Federal Law of 30 March 1998 no. 54-FZ On Ratification of [the ECHR] the legal positions of [the ECtHR] contained in the final judgments of the Court (ECtHR) delivered in respect of the Russian Federation are obligatory for the courts.

In order to effectively protect human rights the courts take into consideration the legal positions of [the ECtHR] expressed in its final judgments taken in respect of other States which are parties to the [ECHR].

However, this legal position is to be taken into consideration by court if the circumstances of the case under examination are similar to those which have been the subject of analysis and findings made by [the ECtHR].

This clear statement of the relationship between Russian law and the ECHR continued until Russia’s illegal annexation of Crimea in 2014. In 2014 the great Judge Anatoly Kovler published an article, written the previous year, on the forthcoming 17 years anniversary of ratification. He concluded “One is reluctant to scrape the bottom to come up with an upbeat conclusion but there is no cause for an apocalyptic vision either. The Russian-European dialogue on human rights is well underway; it is not unlike a tug of war, but its results (albeit modest) are evident.”

But from then on the process of Russian departure from the CoE and ECHR was inexorable.

The impact of the ECHR in Russia

Nevertheless, on 11 January 2016 the PACE, assisted by the Human Rights Centre at the University of Essex, published a report on the impact of the ECHR in various countries.

The report identified a number of instances of positive impact in Russia.1)

- As a result of a pilot judgment (Burdov v. Russia) in 2009 over non-enforcement of a domestic court judgment in favour of the applicant, Russia enacted a Federal Compensation Act, as well as a Federal Law to guarantee the effectiveness of the new remedy.

- In 2005 the RF Supreme Court followed up the 2004 Declaration of the Committee of Ministers and extended journalists’ freedom of expression to criticism of public officials: public officials must accept that they will be subject to public scrutiny and criticism. In 2008 the ECtHR closed a number of applications in view of this change.

- Following Mikheyev v. Russia (2006) and other similar judgments, on account of torture or inhuman and degrading treatment inflicted on persons held in police custody and a lack of effective investigations into such acts, special investigation units were created within the Investigative Committee and tasked with investigating particularly complex crimes by police and other law enforcement bodies.

- There had been progress in the implementation of the ECtHR ’s 2012 pilot judgment in Ananyev and Others v. Russia concerning inhuman and degrading conditions in Russian remand prisons (SIZOs) and the lack of an effective remedy. Russia presented and implemented an action plan as a result, monitored by the Committee of Ministers.

- A number of measures had been taken to remedy numerous violations of the right to liberty, guaranteed by Article 5 of the Convention, owing to unlawful and lengthy unreasoned (or poorly reasoned) detention on remand. Legislative changes were made between 2008 and 2011. Both the CCRF and the RF Supreme Court had emphasized that a suspect or accused may be detained only on the basis of a valid judicial decision. This had been most recently monitored by the Committee of Ministers in 2015.

Pragmatism from the CCRF and resolution of the Russian Hirst

In my 2020 article “Russia and the European Convention (or Court) of Human Rights: The End?” I highlighted what was perhaps the last example of a pragmatic conversation between the CCRF and the ECtHR.

On 19 April 2016, the CCRF rendered a judgment in which it examined the question of the possibility of executing the judgment of the ECtHR of 4 July 2013 in the case of Anchugov and Gladkov v. Russia (on prisoners voting rights, the Russian Hirst v UK) in accordance with the RF Constitution. There were amicus curiae briefs before the CCRF arguing that the problem could be resolved by interpreting the RF Constitution, rather than seeking to amend it, which the CCRF could not do.

The CCRF, with three powerful dissents, disagreed and held that in 1998, when Russia ratified the ECHR, there was no case law under Article 3 of Protocol 1 (right to democratic elections) prohibiting a “blanket ban” on prisoners’ voting. Otherwise, ratification would have contradicted the RF Constitution.

However, the CCRF suggested that, by an amendment to the criminal law, persons detained in Russian “open prison” correctional colonies could be reclassified so that they do not fall within Article 32(2) of the RF Constitution. If this was done, Russia would in effect implement the ECtHR’s judgment. The CCRF emphasized the priority of international law, especially the ECHR, over Russian domestic law, while insisting that it is the final judge on issues concerning the RF Constitution.

Indeed, the pragmatism of the CCRF prevailed and, on 25 September 2019, the Committee of Ministers (CM) of the CoE adopted a final resolution, CM/ResDH(2019)240, which closed the supervision of Anchugov. The closure of the case meant that Russia, taking the advice of the CCRF, had complied with the ECtHR’s judgment, according to the CM’s assessment. The judgment was executed through the introduction to the Russian Criminal Code of a new category of criminal punishment “placement in correctional centers for community work”. Persons detained in this way would have the right to vote and Russia was able to comply with the ECtHR’s judgment. Gleb Bogush and Ausra Padskocimaite wrote a strong criticism of this resolution, claiming that the CM should not have accepted Russia’s compromise.

But that chapter in Russia’s constitutional history has been closed.

References

Prof Bill Bowring, Birkbeck College, Barrister

Russia has been committing a wide variety of heinous war crimes since its all-out invasion of Ukraine, starting on 24 February 2022. These have been documented by many human rights organisations.

On 2 March 2022, the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court (ICC), Karim Khan KC, announced he had opened an investigation into the Situation in Ukraine on the basis of the referrals received. The scope of the situation encompasses any past and present allegations of war crimes, crimes against humanity or genocide committed on any part of the territory of Ukraine by any person from 21 November 2013 onwards. The ICC has a team investigating war crimes committed in Ukraine.

On 17 March 2023, Pre-Trial Chamber II of the ICC issued warrants of arrest for two individuals in the context of the situation in Ukraine: Vladimir Putin and Ms Maria Lvova-Belova (the Russian children’s ombudsman), for the war crime of unlawful deportation of population (children) and that of unlawful transfer of population (children) from occupied areas of Ukraine to Russia. The crimes were allegedly committed in Ukrainian occupied territory at least from 24 February 2022.

Russia is highly unlikely to surrender unconditionally, as was the condition for the Nuremberg trials, and it is equally unlikely that Putin will find himself in the dock at the ICC in The Hague. But the arrest warrants can be seen as a smart move by the Prosecutor, since Putin freely admits the allegations against him, states sympathetic to Russia have become less so, and Putin cannot travel to any jurisdiction where he might be arrested.

But it is notable that the Prosecutor has since 2021 also been carrying out an investigation into war crimes committed in the Occupied Palestinian Territories and Gaza, but so far there have been no indictments or warrants for arrest.

I been asked by USC to write a blog post on “justice for war crimes”. By “justice”, many people mean “revenge”, pure and simple. In the case of war crimes what is meant is the identification, prosecution, conviction and punishment of the perpetrators. The ICC exists to prosecute individuals for war crimes.

The ICC is not part of the United Nations. Like the Geneva Conventions of 1949 and their Additional Protocols of 1977, it was created by the International Committee of the Red Cross, based in Switzerland. On 17 July 1998, 120 States adopted the Rome Statute, the legal basis for establishing the permanent ICC. The Rome Statute entered into force on 1 July 2002 after ratification by 60 countries. 123 states out of 193 members of the United Nations are now members of the ICC, including the UK. But the USA, Russia, India and China – and Israel – are not members. The ICC is therefore hamstrung in a way similar to the UN Security Council, with its five Permanent Members, the victors in WW II, having the right of veto. The United States energetically concludes treaties with as many states as possible, so that US citizens can never be prosecuted for crimes committed on the territory of states which are members.

To repeat, war crimes can be committed by the citizens of any state, if committed on the territory of a state which is part of the ICC system. For example, Ukraine and the State of Palestine.

What are war crimes?

Laws of war, laws of armed conflict, go back to the start of recorded history. In particular the principle that combatants who are wounded or otherwise hors de combat, or who have surrendered, should be spared. The reason is simple. In warfare, neither side can be sure that it will win. Better to lose, and survive, perhaps to fight another day.

But prosecution of individual perpetrators for war crimes is much more recent.

The Nuremberg trials of 1945-46 were only possible (I emphasise) because of Germany’s unconditional surrender on 8 May 1945 to the allied forces of the USSR, which got to Berlin first, the USA, Britain and France.

The German accused were tried for the new crime of against peace (aggression), developed by the Soviet jurist Aron Trainin; war crimes, which already existed in international law as criminal violations of the laws and customs of war; and the new crimes against humanity, since war crimes did not apply to a government’s treatment of its own citizens. The USSR, Britain and the USA agreed that crimes against humanity included “murder, extermination, enslavement, deportation, and other inhumane acts committed against any civilian population”.

Genocide became an international crimes with the Genocide Convention of 1948. And war crimes were codified by the Red Cross in the four Geneva Conventions of 1949. Geneva Convention I for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armed Forces in the Field; Geneva Convention II for the Amelioration of the Condition of Wounded, Sick and Shipwrecked Members of Armed Forces at Sea; Geneva Convention III relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War; and Geneva Convention IV relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War. The four 1949 Conventions have been ratified by 196 states, including all UN member states, both UN observers (the Holy See and the State of Palestine), as well as the Cook Islands. The Conventions were strengthened by two Additional Protocols in 1977. 174 States are party to Additional Protocol I which reinforces the GC IV to the benefit of victims of international armed conflicts. 168 States are party to Additional Protocol II which relates to the protection of victims of non-international armed conflicts.

All States parties to the Conventions are required to make them part of their own domestic law, in the UK the Geneva Conventions Act of 1957. Each Convention contains “grave breaches” with criminal liability, and these are crimes of “universal jurisdiction”. States are under an obligation to prosecute anyone of any nationality who commits grave breaches anywhere, if that person is on their territory. But a warrant issued by the London court in 2008 to arrest Israeli General Almog on his visit to the UK, for the crimes of ordering the demolition of 59 Palestinian homes, failed as the general was tipped off and was able to return home.

The failure of these “universal jurisdiction” laws was part of the impetus for the 1998 Rome Statute of the ICC.

It is not possible to prosecute Putin for the most serious crime, aggression, because this crime was only added to the ICC’s jurisdiction in 2018, and an individual can only be prosecuted for the crime of aggression if they are a national of a state that has signed up to the Court’s statute. So not Russia.

Individual prosecutions for the crime of genocide require proof of genocidal intention, and there have been very few convictions, in cases concerning Former Yugoslavia and Rwanda, in the Tribunals established by the UN Security Council, which have now completed their work. Their case-law is now part of the ICC’s case-law.

I repeat again that the Nuremberg trials were only possible because of Germany’s unconditional surrender. They can be criticised as “victor’s justice”, as there were no prosecutions of Churchill or “bomber Harris” for the fire bombing of German cities; or of Truman for Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

There are private initiatives for the prosecution of Putin and others, but these will have even less teeth than the ICC. In the end, Ukraine must be assisted in every way to maintain its heroic resistance to Russian aggression, and Putin is in an increasingly dangerous situation, for himself and for Russia. He thought he would have a victorious “five day war” in Ukraine, as he did in Georgia in 2008, when the Georgians ran away. If asked, I would have advised him that to take on Ukrainians was a very bad idea.